Last Tuesday, several concerned citizens including LDI volunteers attended the Cook County Commissioners Meeting in regards to issues about Cook County Animal and Rabies Control. We try to keep our supporters and fans up to date on issues that affect getting lost dogs back to their rightful home. As many of you know, Lost Dogs Illinois supported the petition to reform Cook County Animal and Rabies Control.

Here are the four public statements in support of the petition:

Public statement #1

My name is Susan Taney, Director of Lost Dogs Illinois, a not for profit organization which provides a free service to help families find their lost dogs. Our FB page has over 100,000 fans and since our inception in December 2010 over 16,000 dogs have been reunited with their families

A year ago, I, along with numerous others, made public statements in regards to the Department of Cook County Animal and Rabies Control. Commissioner John Fritchey heard our concerns and initiated the Inspector General report.

I would like to address statements that were made at the budget meeting and ask if it is time to reconsider the department’s mission. Currently the mission is to provides health protection to the residents of Cook County through preparation, education, rabies vaccination and stray animal control

In the last few decades, the status of dogs has been elevated from the barnyard, to the back yard and now to our bedrooms. Our dogs are now loved family members.

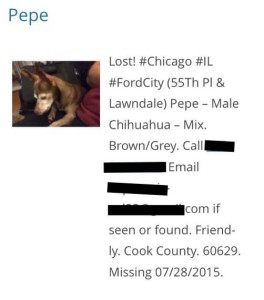

With the maze of stray holding facilities in Cook County, it is very difficult for families to find their missing dogs. Approximately 50 municipalities are contracted with Animal Welfare League; 14 with Golf Rose Boarding Facility; 5 with Animal Care League and with other municipalities using vet clinics, animal shelters, police departments. etc. to hold stray dogs. Many dogs are not reunited with their families. They are adopted out, transferred to another shelter/rescue or euthanized. A centralized database would make it easier for families to find their lost dogs and assure more dogs are reunited. A simple FREE solution is to use Helping Lost Pets, centralized national map based website. The county and other municipalities could start using it now. Lost Dog Illinois along with over 25 states have already partnered with HeLP.

Commissioner Fritchey commented on the kill rate of Animal Welfare League. In 2014 Animal Welfare League took in approximately 14,500 animals and euthanized approximately 7,900 animals. 53 municipalities and Cook County contract with AWL. The bar of excellence should be set high for AWL in getting lost dogs home and saving lives.

Recently CCARC added a Lost Pets section to their website. After reviewing the website there are many stray hold facilities that are not listed. Animal Care League as well as vet clinics and police departments that act as holding facilities in Cook County have been omitted. Also, our organization Lost Dogs Illinois is not listed as a resource to help families find their lost dogs. Our site provides free flyers, tips, resources and community support to help families find their lost dogs.

I am not discounting the importance of rabies and public safety but I really believe it is time to reexamine the mission of this Department and reorganize CCARC to provide better services. Cook County is the 2nd largest county in the US, we should be proud to offer an efficient way for owners get their loved family members back.

Public Statement #2

My name is Becky Monroe, LDI Volunteer

I think that the issues with Animal Control can best be expressed by reading a piece by the Chicago Tribune Editorial Board published Sept 8 entitled, “Why lost pets stay lost in Cook County.” The piece started by talking about what to do if you’re trying to find your lost pet.

Reading from the article:

“Don’t expect much help from Cook County’s Department of Animal and Rabies Control. It doesn’t operate a shelter and doesn’t consider reuniting lost pets with their families a big part of its mission. In a report last month, the county’s inspector general made a good case that it ought to, and we agree. Especially since the IG’s six-month review left us shaking our heads at what the department actually does.

Animal Control is about rabies, mostly. It gets most of its funding from the sale of rabies tags — and spends much of that money to pay employees to type the rabies tag data into a very old computer system.

There are 22 full-time employees, and 13 of them spend most of their time processing tags, often earning comp time for working during their lunch hours, according to the IG’s report.

Most of the data is submitted by clinics, shelters, veterinarians and rescue groups that perform the actual rabies vaccinations, but Animal Control’s system is so dated that the information can’t be uploaded easily, if at all. So staffers do it by hand. If this reminds you of the Cook County clerk of the circuit court office, join the club.

The IG recommends a web-based system so veterinarians and others can input the data themselves, freeing up resources for more meaningful services (like helping you find your dog.)

The office is closed nights, weekends and holidays, and the IG’s report notes that law enforcement agencies throughout the county complain that they can’t access rabies data or find an animal control officer except during banking hours.

There are six employees who patrol the unincorporated area for strays. Their workday includes time spent commuting to and from work in their take-home government vehicles. For one employee, that’s three hours a day. If heavy traffic means their door-to-door workday lasts longer than eight hours, they get comp time.

What do they do in between? The report doesn’t say, exactly, but it sounds rather aimless.”

The Tribune Editorial mirrors another article that the Tribune ran on August 4 about Animal Control failing to pick up a dog after they were notified by the Sheriff’s Office on July 13.

Reading from the article:

“The dog was in the locked garage when officers arrived July 13 to evict two young men from a foreclosed house in the 11200 block of Worth Avenue. Finding that the men had moved out, officers posted an eviction notice and called the animal control department to remove the dog, according to the sheriff’s department.

But last week, Frank Shuftan, a spokesman for County Board President Toni Preckwinkle, denied that such a call was placed, saying in an email to the Daily Southtown that animal control double checked its call log for that day after the Southtown story appeared and found no record of such a call from sheriff’s police.

But the sheriff’s department released a tape of a July 13 call in which a woman is clearly heard saying, “Cook County Animal Control, may I help you?” A sheriff’s officer then says, “Cook County Sheriff’s Police calling” and that there’s “a dog to picked up from an eviction” and giving the address in Worth.

“It’s a German shepherd in the garage,” the officer says, giving the name and phone number of the receiver, the person representing the bank, who would be waiting for animal control at the garage.

Animal control apparently never sent anyone to the house.”

How many bad news stories will it take to get this Board to make meaningful changes at Cook County Animal Control? It seems obvious to everyone who has had interaction with Cook County Animal Control that this department is a disaster. We are calling upon the County Board to stop ignoring this issue.

http://www.chicagotribune.com/suburbs/daily-southtown/news/ct-sta-cook-county-dog-snafu-st-0805-20150804-story.html

http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/opinion/editorials/ct-animal-control-audit-pets-edit-0909-20150908-story.html

Public Statement #3

My name is Kathy Pobloskie and I am an advisor with Lost Dogs Illinois. Thank you for allowing us this opportunity to speak today.

The vast majority of animals in shelters come from two sources. Strays, which are lost pets, and surrenders. We are here today to talk about lost pets. In fact, the ASPCA estimates that 40 – 60% of animals in shelters are lost pets. Most of these pets do not need a new home, they simply need to go home.

Proactively reuniting lost pets with their owners should be one of the main focuses of animal control departments. When barriers prevent people from reclaiming their lost pets, the system fails. I would like to talk about one of those barriers. That barrier is inconsistency.

Currently the range of fees for Cook County stray holding facilities vary from $7 per day on the low end to $36 per day on the high end. Microchips (which are required to reclaim) range from $20 to $35 and does not include the additional cost of registration. Vaccines can cost up to $29 per vaccine. Each municipality also has it’s own impoundment fees, fines, licenses, etc. One of the main reasons for dogs being left at a shelter is cost. By the time the owner locates them, they cannot afford to reclaim them. It is not unusual for costs to reclaim your dog to be well over $100 for a 24 hour stay at “the pound”. Then of course, there is a strong likelihood that your dog will come down with an upper respiratory infection common in crowded municipal shelters. Add veterinary costs on top of the above fees also.

Start to multiply this by a few days and pretty soon you could be looking at what could equal the car payment or rent or prescription costs or groceries for the family. Don’t forget – not everyone has a credit card or money in the bank. They might need to wait until the next payday to come and get their dog. Pretty soon, it’s become more than they can afford.

Cook County stray holding facilities are also inconsistent in their stray holding periods. They range from 3 days to 7 days. Many people work two jobs or jobs that prevent them from getting to the facility during normal business hours to check to see if their dog is there. Your dog cold be adopted out, transferred to a rescue, or even worse, killed, because you did not figure out the “system” in time. It is not uncommon for lost dogs to travel and cross into a different jurisdiction.

Standardizing fees and stray holding periods to enable the highest number of lost pets be reclaimed by their owners would go a long way to improving Cook County Animal Control. Pets are family members. Give citizens a chance to keep their families whole. This will also help save the more than 9000 animals that are killed in America’s shelters every day.

Public Statement #4

Public statement to the Cook County Commissioners on Nov. 3, 2015, regarding Cook County’s Animal and Rabies Control department and the OIIG audit and report of Aug. 21, 2015, delivered by Lydia Rypcinski, private citizen of the County of Cook and City of Chicago.

Thank you for granting time to speak before you today regarding Cook County’s Animal and Rabies Control department.

Unfortunately, it may be the last day that some beloved pets will ever know in this world. They have become lost; their owners don’t know where to find them within the labyrinth of animal control agencies that operate in Cook County; they have been given only a few days to either be claimed or adopted; and the municipal and private shelters contracted to house these animals are understaffed, under-resourced, and filled to overflowing.

So these lost pets will be killed in the name of operational expediency.

It does not have to be this way. While it is true that the mission of animal control historically has been to protect people first and animals second, much has changed in the way humans interact with what we now call “companion animals” since the passage of the Cook County Animal and Rabies Control Ordinance in 1977.

It is disheartening to see CCARC’s administrator declare, “Pet reunification is not part of the department’s core mission.” She may be interpreting the letter of the law correctly while missing an essential truth in this new era: that people view their pets as extensions of their families and want – and expect – government attention and assistance when one of them is missing.

To ignore that change in the public’s perception of the services a successful animal control operation should provide is to do a disservice to the very taxpayers that support the department and office.

I call your attention to this excerpted passage from a book by Stephen Aronson entitled, “Animal Control Management: A New Look at a Public Responsibility” (Purdue University, 2010):*

“Differences in opinion notwithstanding, animal control officials need to communicate with, cooperate to the extent possible, and garner support of those who have a perceived interest in the welfare of the animals in the community . . . [Animal control] must reach out to those it serves and work with those who want to offer their help to make the community a better place for people and animals to coexist.”**

I do not believe this communication and outreach exist today, even within the department itself. When I hear Dr. Alexander state that the Animal Welfare League, which is contracted to house County strays, is in Chicago Heights when it is actually 20 miles north in Chicago Ridge and about a 15-minute drive from her headquarters in Bridgeview, I have to wonder if she has ever even visited it to see how County money is being spent. Is she aware that AWL’s own stats reveal that every animal taken there by County animal control in 2014-15 had a better than 60 percent chance of leaving that facility in a garbage bag, headed for a landfill or crematory?

Surely County money can be spent more productively and rewardingly, to reunite these animals with their families, even if it isn’t part of the department’s “core mission.”

In light of these observations, I urge the Commissioners to adopt and implement all the recommendations made in the Inspector General’s Aug. 21, 2015 audit and report, to make Cook County Animal and Rabies Control more fully responsive to the changing needs of its community. I would like to point out that you have a wellspring of animal welfare professionals and volunteers available in this area, whose talents and resources could be tapped to help bring these changes about. Please avail yourselves of these people and organizations. Thank you.

* Aronson is a former local and state government worker with experience in animal control operations.

**Chapter Nine, “Interacting with Public and Private Entities and the Citizenry,” pp. 188-189.